Stanley Gutu

Masvingo–Winter had just arrived in mid-May 1978 as the war of liberation against the Ian

Smith-led Rhodesian Front was intensifying to a crescendo.

A small group of Zimbabwe National Liberation Army (ZANLA) fighters operating in the Dewure Native Purchase Area of Gutu district in Masvingo province cautiously slipped into the local farming area from their mountain hideouts to instruct their mujibhas to spread the message that a pungwe was to be held at John Kamungoma’s farm, which was one of the many farms owned by black Africans under colonial land tenure laws.

Mujibhas were adolescent boys recruited to run errands on behalf of freedom fighters, and pungwes were deep-night political conscientisation vigils meant to mobilise the masses to support the liberation struggle.

The Kamungoma pungwe started at around 9pm on May 14 with one guerrilla known to this day only by his nom de guerre ‘Comrade Double Killer’ leading the frenzied crowd into song and dance.

Then suddenly, and without warning, the Rhodesian soldiers fired into the gathering; triggering panic and pandemonium.

Survivors of the massacre say a detachment of the Rhodesian Army carrying out reconnaissance work in the area had gotten wind of the planned vigil.

The soldiers climbed a big tree in the vicinity and stealthily concealed themselves before launching their indiscriminate heavy machine gun attack on the crowd. They then climbed down the tree and used a searchlight to track fleeing civilians before shooting them one by one.

By dawn, a ghastly horror of 104 bodies, including that of Comrade Double Killer, were found in streams of blood, all mangled together with survivors that were writhing in pain. Seventy-seven year-old Patricia Mapfumo was part of the crowd that attended the pungwe where the massacre occurred.

She is one of the victims of the attack who are still alive, having survived what is known as the Kamungoma massacre, and has endured over four decades of trauma after suffering multiple injuries during the attack.

According to government records, there were over 100 injured survivors altogether, with 32 of them still alive.

An investigation, which was facilitated by the Information for Development Trust (IDT), a non-profit media organisation promoting investigative journalism in Zimbabwe and the SADC region, revealed that the victims such as Mapfumo have been largely neglected despite there being a law providing for their fair compensation.

Though some of the survivors receive a disablement pension in terms of section 8 of the War Victims Compensation Act [Chapter 11:16], they say the money is too little to make a difference.

The investigation, which was prompted by pleas from concerned Kamungoma community members to shed light on the plight of the survivors, found that some of them receive monthly pensions of between US$100 and US$120. However, those with less visible disabilities and scars are not receiving anything.

Mapfumo, who suffered gunshot wounds on the chin, palm, waist, leg and eventually had her right hand amputated while her lower jaw was reconstructed, also lost her baby in the attack.

Other victims of the massacre that are still alive include Joyce Nyandoro, Chipo Mukuze, Samuel Mukwembi, Simon Mukwembi, Patricia Machera, Papson Chiwara, Memory Zishate, Andrew Mapfumo, Davison Dedzera, Ratidzai Nikisi, Johannes Chikuvire, Ephraim Chikozho, Anna Mutikani and Farai Chikwiro.

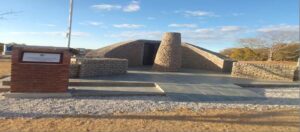

President Emmerson Mnangagwa in April this year officially unveiled the Kamungoma Liberation War Memorial Site as part of efforts to memorialise the tragic events, but for the survivors it could be a case of too little too late.

Sources from the Ministry of Home Affairs and Cultural Heritage sources said about US$120 000 was used to build the memorial site. They said the site was built under a memoralisation programme that saw government erecting similar structures in Lupane’s Pupu area, Chinhoyi and Old Bulawayo.

‘I will never heal’

“I will never heal,” Mapfumo said as he lamented the fact that the survivors never received adequate socio-economic and pycho-social support after the horror attack.

“I have always struggled to find the basics of life, and I feel something better could be done for us to improve our lives.”

The survivors, including Mapfumo, are found in the Kamungoma community, which is made up of farms that were set aside for Africans by the colonial regime through the then Land Apportionment Action of 1930.

The farms average 30 hectares each, but the subsistence farming activities are largely non-mechanised and poverty is palpable.

Over the past two years, many families in the community lost entire cattle herds due to frequent outbreaks of theileriosis and foot and mouth diseases.

Mapfumo’s circumstances are not different from those of other survivors as her family struggles to put food on the table.

She lives with her daughter Vongai (57), who lost her right forearm during the attack and still suffers from panic attacks.

“Although I have come to accept my physical condition, it remains a traumatic experience and the horrific images of the attack are still fresh in my mind,” Vongai said.

“I think we should be living better lives because of the sacrifices we made and the blood and limbs we lost, but that is not the case.

“I lost an arm and that means I cannot be my whole self because of severe limitations in the nature of the work that I can do,” said Vongai.

Compensation fund looting

In November 1980, months after Zimbabwe’s independence, Robert Mugabe’s government enacted the War Victims Compensation Act “to provide for the payment of compensation in respect of injuries to or the death of persons caused by the war, and to provide for matters incidental to or connected” to the liberation war.

Section 4 of the War Victims Compensation Act [Chapter 11:16] entitles citizens of the country to apply and make claims for disablement pension if their injuries were directly or indirectly caused by the war between 01 January 1962 and 29 February, 1980.

Section 8 of the act creates categories of victims based on the extent of injuries sustained.

It stipulates that the disablement pension value that each category of victims is entitled after a commissioner has made an assessment and determined the extent of disability emanating from the injuries.

Those determined to have suffered 100% disability and have changed or downgraded their normal occupation are entitled to the highest disablement pension.

In August 1997, a judicial commission of inquiry into the fraudulent disbursement of Z$1.5billion from Zimbabwe’s War Victims’ Compensation Fund started probing the abuse of the fund. The investigation followed complaints that top Zanu PF politicians, war veterans, senior government officials, and military leaders had, from as far back as 1995, defrauded the fund through inflated compensation claims.

The commission of enquiry was headed by the then judge president Godfrey Chidyausiku.

Chidyausiku’s commission found that the then war veterans’ leader Chenjerai Hunzvi, a medical doctor, certified that dozens of high ranking ruling party officials should be paid out for non-existent war injuries. Hunzvi also signed his own fraudulent medical certificate as well as false claims by relatives.

Former president’ Robert Mugabe’s Reward Marufu was paid nearly $1 million in compensation for ‘sustaining a scar on the left eye, ulcers, recurrent aching feet and arms and persistent backache and post-war stress syndrome’.

Then Rural Resources and Water Development minister Joice Mujuru received $389 472 for ‘poor vision’ and ‘mental stress disorder.’ Government ministers, security chiefs and other high ranking Zanu PF were said to have claimed that they had disabilities of over 80%.

It has now emerged that amid the looting frenzy, the Kamungoma massacre were getting pensions of between US$100 and US$120 depending on the severity of their injuries, a drop in the ocean in a hyperinflationary environment.

Sesedzai Maharure (62), who was shot on her hands, waist and legs on the night of the Kamungoma massacre, said she often suffers paralysing pain during winter, but has never been given any compensation.

“I expected a better life, but I am getting old and tired. As a war victim, I expected enough compensation to help me to turn around my life and get the medical assistance I need, but it didn’t happen,” Maharure said.

“This year is particularly painful because of the drought and we are hungry,” Maharure said.

She said she made several applications for compensation since independence, which were all in vain.

Bullet lodged in head

Petros Makwanya (62) said he has been living with a bullet in his head after doctors concluded that any surgery to remove it would result in death.

He was shot in the head, legs and arms. Makwanya spent several months in hospital after the attack that also claimed the life of one of his brothers, Naphtali.

Makwanya, who stays with his wife and son, walks with a limp and his speech is slurred.

“I sometimes take painkillers, but they just give me relief for a short time,” he said while holding the x-ray image showing the bullet stubbornly ensconced in his cranium.

“It’s an insult to (my brother’s) memory that his grave is cracked like that, but there is little I can do because I don’t have much. The government promised to erect proper tombstones for all those who died that terrible night, but it has not happened.”

Naphtali’s grave, with a downward gaping crack on the headstone, is almost hidden in thick grass and shrubs. Most of the graves of the victims that perished on the night of the massacre are in similar condition.

Makwanya’s son Simpson, who was born in 1991, has almost lost hope of ever getting a formal job because his parents cannot afford to pay fees for him to enrol at a teacher training college.

Mnangagwa acknowledged that surviving victims of the massacre were suffering from trauma, wounds and painful memories when he officiated at the unveiling of the Kamungoma Liberation War Shrine.

“The indiscriminate attack saw teenagers and women, some breastfeeding mothers, losing their lives,” he said.

“The deceased were buried in shallow graves.

“The Ministry of Home Affairs and Cultural Heritage, as well as the National Museums and Monuments of Zimbabwe, among other stakeholders, are directed to broaden the memorialisation of the Kamungoma Liberation War Shrine and remodel the graves of all those who were killed.”

He, however, did not elaborate on how the government would look after the victims of the massacre.

On the day, the 32 survivors were paraded and were each given a small grocery hamper.

‘It’s work in progress’

Musarurwa Dondofema, the Kamungoma Liberation War Memorial acting custodian, admitted that the survivors’ welfare was neglected.

“They face many challenges and we have raised the issue with the relevant authorities to make sure that their plight is addressed. It is still work in progress,” Dondofema said.

He claimed the outbreak of Covid-19 disrupted plans to rehabilitate the graves although it has been over two years since the pandemic ended without any work being done.

“All the tombstones are there in Harare, but the process was delayed due to the Covid-19 outbreak.

“We hope things can start moving now,” added Dondofema, whom locals recognise as the de facto local representative of the Kamungoma massacre victims.

Dondofema would, however, not reveal where exactly in Harare the tombstones located were being kept and efforts to verify Ministry of Home Affairs and Cultural Heritage drew blanks.

Gutu South Member of Parliament, Pupurai Togarepi, who himself claims to have been a war collaborator, said the government was taking steps to give Kamungoma massacre victims comprehensive compensation packages.

“Many war collaborators are yet to get any form of compensation,” the Zanu PF MP said.

“Money is never enough, but we are going to look for ways by which we can improve their lives.

“I will look for resources to make sure that we start projects for them.”

Togarepi, who doubles as the Zimbabwe Liberation War Collaborators Association (ZILWACO) chairperson, claimed the victims were now getting recognition.

“There is a lot that still needs to be done but we are grateful that they have been put in front of the line to benefit from the compensation, which is a sign that the government recognises the collective efforts made by everyone during the liberation struggle,” he added.

Victims of corruption

They can be considered victims of the unbridled corruption that characterised the War Victims Compensation Fund until around 1995 when it was discovered that it had been looted by former fighters, primarily service chiefs, senior army commanders and senior civil servants.

The payments were halted in 1997 following a public outcry, leading to the setting up of the commission of inquiry.

That same year Mugabe’s regime was forced to pay unbudgeted pensions of $50 000 to each war veteran following pressure from the ex-fighters, who were angered by the looting of the War Victims Compensation Fund.

In 2022, Mnangagwa’s government said it was planning to pay one-off gratuities and monthly pensions to a new batch of 160 000 war veterans, war collaborators and ex-political prisoners who missed out during the first round of compensations.

This story was commissioned by Information for Development Trust (IDT) and originally published by The Zimbabwe Independent.

Comments are closed.