Kelvin Wilson Kasiwulaya

Gweru —The noise has somewhat died down, but the problem is still there, though far smaller than three decades or so ago.

In the 1980s and 1990s in particular, hardly a day would pass without news of people or livestock being blown up by anti-personnel mines in villages in Mashonaland Central, close to the border with Mozambique.

Between 1974 and 1979, Ian Smith’s Rhodesian Front security forces planted an astonishing number of anti-personnel (AP) mines to counter guerrilla fighters during the war of liberation.

Estimates from HALO Trust—a global leader in mine clearance—and Zimbabwean historian Martin Rupiah suggest that over one million landmines were strategically placed along the borders with Mozambique and Zambia, creating some of the most densely mined regions in the world.

HALO is responsible for clearing 83% of all mines in Zimbabwe.

In the worst-affected areas today, there are approximately 5,500 mines per linear kilometre, equating to up to three mines for every metre of terrain.

According to HALO Trust, minefields stretched across about 240 linear kilometers, creating vast, unmarked danger zones.

Since then, over 1,500 people have lost their lives or suffered injuries due to landmines, while approximately 120,000 livestock have perished.

The ongoing threat of unexploded ordnance has trapped communities in cycles of poverty and fear.

In 2023, the Mine Action Review reported that five of Zimbabwe’s 10 provinces remained heavily contaminated with AP mines.

In 2022, some land had been cleared, reducing the affected area from 23.5 km² to just over 18.3 km².

However, six minefields remain along Zimbabwe’s borders with Mozambique, with another one further inland in Matabeleland North.

According to the United Nations, there are more than 600 different types of landmines, grouped into two broad categories—anti-personnel and anti-tank landmines. Despite a 1997 international treaty banning their use, over 60 million people worldwide still live in danger, with Zimbabwe being no exception.

The majority of these mines are designed to maim rather than kill. These small, camouflaged devices, which detonate when triggered by pressure or proximity, pose particular threats to children.

The danger is compounded by the fact that mines are often hidden in grass, buried underground, or even attached to trees, making them difficult to detect and remove.

Today, 29 square kilometers of land remain contaminated, putting more than 85,000 people at risk as they navigate their daily lives in search of basic needs such as clean water, healthcare, and education.

Agricultural land is also heavily affected, depriving families of their livelihoods and making post-conflict rebuilding even more difficult.

Landmines in Zimbabwe

A Dangerous Legacy

Minefields in Zimbabwe are uniquely dense and complex. Initially, the Rhodesian military laid mines in several belts. In one section, dense AP mines were buried in the ground, while in another, a locally-made mine called the “Ploughshare” was mounted on posts and attached to tripwires, according to HALO.

As the war progressed, fences and cleared areas were abandoned, and mine-laying units began employing different patterns.

HALO Trust explains that the posts for the Ploughshares have since rotted, and their tripwires have eroded.

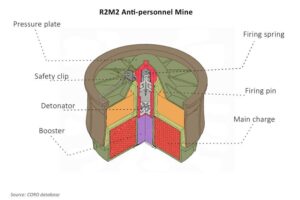

Some of the most dangerous minefields contain the R2M2—a minimum-metal South African mine that is particularly difficult to detect but remains lethal even 50 years after being laid.

The only metal components of the R2M2 are a pin that strikes the detonator and a small spring, both sealed in plastic.

This design makes it challenging to detect with metal detectors, and the mine remains highly dangerous even after decades in the ground.

The Ploughshare, known as a “directional fragmentation” mine, was designed to project steel fragments across a wide area.

While the posts and tripwires may have decayed, the mines themselves remain hazardous to handle and were often safeguarded by buried anti-personnel mines, according to HALO.

US Role in Demining

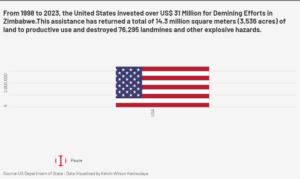

As early as 1998, the US recognised the urgent need for demining initiatives in Zimbabwe, launching an extensive plan for conventional weapons destruction.

The US Department of State, through the Office of Weapons Removal and Abatement (PM/WRA) in the State Department’s Bureau of Political-Military Affairs, has spearheaded humanitarian demining projects in Zimbabwe, partnering with organisations like the HALO Trust to clear mines and restore access to vital land.

The PM/WRA sponsors the HALO Trust. Since 2012, the United States has provided over $7.6 million for humanitarian demining in Zimbabwe, an investment that plays a critical role in helping local communities recover from the lasting effects of landmines and unexploded ordnance.

The United States is the world’s leading financial supporter of conventional weapons destruction, providing more than $5.09 billion in assistance to over 125 countries and areas since 1993, while the European Union contributed $2.1 billion, Canada $1.5 billion, and other countries contributed a combined $1.9 billion.

The funding aids in clearing hazardous land and supports essential programs for the medical rehabilitation and vocational training of landmine survivors. It also funds community outreach to reduce future injuries and the development of technologies to tackle these dangers, facilitating recovery in countries still affected by the aftermath of conflict.

The PM/WRA leads efforts to address the destructive impact of landmines, unexploded ordnance (UXO), and other weapons of war. Its work promotes global peace and security while restoring land for civilian use by removing explosive hazards and curbing the spread of illicit weapons.

Since 1998, the US has dedicated $31 million specifically to demining efforts in Zimbabwe, with a substantial portion of this funding channeled through the HALO Trust.

Since the collaboration began in 2013, this partnership has cleared approximately 76,295 landmines and reclaimed over 14.3 million square meters (nearly 3,536 acres) of land, significantly reducing the landmine threat in regions such as the Mt. Darwin and Rushinga Districts.

This funding has been crucial in providing local communities with the safety they need to access essential resources, cultivate crops, and begin rebuilding their lives.

In 2020, the US allocated $3 million to eliminate 6,541 landmines and recover 1.44 square kilometers of land.

The United States provided $3.25 million to clear landmines and destroy weapons in Zimbabwe from late 2021 to late 2022, and nearly $29 million for explosives and weapons destruction in Zimbabwe since 1998.

In total, HALO has cleared over 1,050 acres (142 hectares) of land in Zimbabwe—an area more than three times the size of London’s Hyde Park.

According to the US State Department’s “To Walk the Earth in Safety” report of 2023, this area has been made safe for local communities, allowing them to access essential resources, cultivate crops, and rebuild their livelihoods.

Since 1993, the United States has provided more than $594 million to support conventional weapons destruction programmes throughout Africa to return previously contaminated land to safe and prosperous use, prevent the illicit diversion of small arms and light weapons,and support government efforts to secure their stockpiles.

HALO Trust’s Journey to Make Zimbabwe Landmine-Free

Since 2013, the HALO Trust has made significant progress in clearing landmines and making Zimbabwe’s land safe again. One of their major accomplishments came in 2016, when they cleared a minefield around Chivere village situated close to the Mozambican border in Mashonaland West province.

A team of 112 Zimbabwean deminers worked for 18 months, clearing 276,063 square meters of land—equivalent to over 68 football fields—and destroying 11,546 mines.

This effort brought much-needed relief to the local villagers, who were finally able to use their land without fear.

In 2017, HALO Trust took on an even bigger project, clearing a 29-kilometer-long minefield in northeastern Zimbabwe.

The project benefitted over 14,000 people, with a total of 14,742 mines cleared. Some minefields were particularly dangerous, with up to 5,500 mines per linear kilometer, posing a significant challenge to the deminers and local communities alike.

One of the biggest milestones came in November 2021, when HALO became the first organization to declare an entire district mine-free. The government officially declared the Mount Darwin area, four hours north of Harare in Mashonaland Central Province, completely safe from mines. This achievement marked a historic moment in the country’s demining efforts, ensuring safety for thousands of residents.

In 2023, Zimbabwe destroyed a record 37,260 landmines. However, the country has had to push back its landmine clearance deadline to 2028. HALO is responsible for clearing 83% of the landmines.

According to HALO Trust, to date, they have cleared an impressive 8 million square meters of land—more than two and a half times the size of Central Park in New York City. Today, HALO’s work is concentrated in the northeastern part of the country, where more than 470 local men and women are employed as de-miners. From 2013 to 2024, they have cleared over 210,000 landmines—an average of nearly four mines for every person in the region.

A Turning Point: Transformative Efforts of HALO Trust

In 2013, the HALO Trust began its operations in Zimbabwe, focusing on the critical goal of making the country landmine-free by 2025.

HALO Trust has been a driving force in addressing this legacy of conflict. They have employed local de-miners and harnessed community resources and expertise to tackle this monumental challenge.

By 2017, HALO Trust had successfully cleared the minefield around Chivere village, creating a transformative shift in the community.

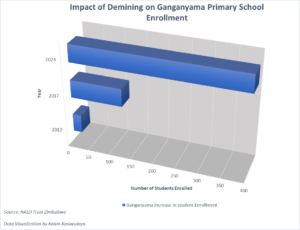

One of the most profound outcomes was the dramatic change at Ganganyama Primary School. With the area now safe, student enrollment soared from just 20 to over 120.

Headmaster Christopher Ngwerume noted, “Each and every child has a right to attend school, and it is possible because the landmines have been cleared.”

The importance of this achievement goes beyond numbers—it’s about ensuring that the next generation can learn and thrive without fear of landmine accidents. Ganganyama School today has over 400 pupils enrolled.

Thanks to demining efforts, their walk to school has been reduced from two hours to 45 minutes.

A Community’s Struggle

For families living near minefields, accessing healthcare services is a dangerous ordeal. Clinics that could serve local populations often sit beyond safe reach, forcing individuals to undertake perilous journeys over mine-laden terrain, sometimes traveling up to 25 kilometers to reach the nearest facility, a daunting distance for vulnerable groups such as pregnant women and children.

.

Education Under Threat

In Chisecha, in Mt. Darwin District in Mashonaland Central, a primary school with about 1,000 pupils faced risk, just 200 meters from the minefield, as children often have to traverse dangerous paths to reach class.

Schools located near minefields expose students to life-threatening conditions.

There have already been seven recorded non-fatal accidents near the school, further highlighting the hazardous conditions.

At Ganganyama Primary School next to the village of Chivere, over half of the 400 students faced similar fears.

Located just 300 metres from one of the densest minefields in the world, parents worried daily about their children’s safety. Many students would walk four kilometers to school, with the minefield directly in their path. Families faced the daily struggle of ensuring their children could reach their classrooms without peril.

Water Access Compromised

The Mukumbura River, the only local water source for villages near the border in Mt Darwin, poses another challenge. The presence of landmines deters families from approaching these vital points, forcing them to undertake long, dangerous hikes to find clean water. Accessing this critical resource becomes not just a challenge, but a significant risk.

Agriculture is essential to many communities in Zimbabwe, and the presence of landmines severely disrupts this lifeline. Fields that were once fertile now lie fallow, as farmers are unable to cultivate crops near the minefields.

In regions like Rushinga, families struggle to make ends meet. Angela, a local resident, shared her plight: “We had to move to the northern edge of the village for more space, but now we live less than 50 meters from one of the deadliest minefields.”

The impact of landmines extends to the local economy. Business opportunities dwindle as entrepreneurs struggle to establish viable commerce in areas near minefields. Fear and uncertainty deter customers from visiting local markets, while compromised transportation routes complicate the delivery of goods, increasing costs and risks for local businesses.

Local residents face constant challenges, living in a cycle of poverty exacerbated by landmines. The dire need for arable land has led some farmers to attempt clearing fields themselves, often resulting in tragic accidents.

In this complex web of challenges, families must navigate daily life while contending with the persistent threat of landmines.

Liberating Communities Through Mine Clearance and Its Broader Impacts

The removal of landmines has proven to be more than just a safety measure—it has been a catalyst for significant social, economic, and healthcare improvements in Zimbabwe’s most affected communities. Areas once immobilised by the silent threat of landmines are now witnessing the rebirth of vital infrastructure and local economies, offering a glimpse into a future once considered unattainable.

Health Accessibility: Mafigu Clinic’s Life-Saving Mission

At Mafigu Clinic in Rushinga district, Mashonaland Central, Massi Kenyere reflects on how mine clearance has directly improved health service accessibility. “Before the landmines were removed, the closest clinic was 25 kilometers away,” she explains. This distance was especially perilous for pregnant women requiring immediate medical care.

Mafigu Clinic is now positioned in an area previously deemed too dangerous for habitation, offering essential healthcare services not only to local residents but also to individuals from neighboring Mozambique.

The accessibility of healthcare, once hindered by the looming threat of landmines, has contributed to a reduction in preventable deaths and improved overall community health outcomes. “Our presence here has helped reduce death rates,” she added.

Economic Revitalisation: A New Era for Katiza Village

Mine clearance has also transformed the economic prospects of communities, particularly through enhanced agricultural productivity.

Economic revival sparked by mine clearance is visible in Katiza village, where families like Miriam’s have seen a dramatic improvement in their livelihoods. “Since HALO made the land safe, life is very different,” Miriam shares.

Her family has expanded its farming operations by three hectares, increasing household income by $200 annually.

But perhaps the greatest benefit is the psychological relief that comes with no longer living in constant fear of landmines.

For years, Miriam’s family had been trapped in a cycle of fear and loss. They lost four cattle to the mines and were unable to fully utilize their land. “Every day, I would walk my children to school along a narrow path that weaved through the minefield, always making sure we passed through safely,” Miriam recalls. But now, with the land cleared, her family can farm more land, earn more, and live without fear.

While the safety of land provides new economic opportunities, the emotional impact of mine clearance is just as profound. “I can sleep at night knowing my children are safe,” Miriam says, a sentiment echoed by many in her village.

Community Transformation: Reflections on Safety and Freedom

Local leaders are echoing the broader community sentiment of liberation. Headman Foya from Foya Village in the Mt. Darwin district highlighted the profound shift in attitudes since landmines were removed. He noted that his community had suffered from lost livestock and lives for years, but with the mines cleared, the potential for economic development and safer living conditions is now a reality.

“We have lost much livestock and many people over the years. Once the land has been cleared, it can be used productively,” he reflected, adding that land clearance has created the potential for productive use of once-dangerous land.

This renewed sense of hope is shared by other communities that have witnessed firsthand the benefits of landmine clearance. Once-deadly land has been turned into productive space, allowing for economic activities like farming and infrastructure development, which were once too dangerous to undertake.

The Road Ahead: A Mine-Free Zimbabwe by 2025

While the Mt. Darwin and Rushinga District villages are witnessing the benefits of landmine clearance, large areas of Zimbabwe, particularly along the northern border, remain contaminated.

Though progress has been made, the country’s mine clearance efforts are far from complete.

HALO Trust aims to achieve a mine-free Zimbabwe by 2025, but this goal requires continued investment and international support.

Zimbabwe destroyed a record 37,260 landmines in 2023, the highest number for the year, according to HALO.

Despite this achievement, the country has had to extend its deadline for completing all landmine clearance to 2028.

Comments are closed.