Sofia Mapuranga

Parched rural Buhera in Manicaland province, southeastern Zimbabwe, witnessed rare pomp and glitz in December 2022 when President Emmerson Mnangagwa came down with a high-powered delegation.

The entourage included the vice president, Constantino Chiwenga, and the third most powerful figure in government, Oppah Muchinguri, who is Defence minister, but also the ruling Zanu PF national chairperson.

Also presented was Mines minister, Winston Chitando, a whole array of top government officials and a swarming team of security details, some of who had camped in the area well before the event.

They had come for the ground breaking ceremony for the Max Mind Zimbabwe lithium mine, Sabi Star, which is Chinese-owned.

Thousands of villagers barely accustomed to the sight of hundreds of modern off-roaders and wailing sirens gathered for the event with excitement, hope and awe.

But also tucked away within the huge crowds were those that followed the event with anxiety, trepidation and silent but seething disapproval.

They were mostly the villagers who had been displaced by the lithium project from Ward 12 that incorporates the Tagarira and Mukwasi villages under Chief Nyashanu.

US$130m investment

Sabi Star Mine is a US$130 million-dollar lithium mine owned by Chengxin Lithium Group of China, in partnership with Max Mind Investments Zimbabwe Private Limited.

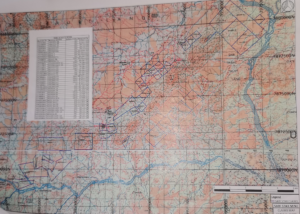

It is located some 40 km east of the Murambinda business centre in Buhera, on the Odzi belt that is well known for such minerals like gold, diamonds, gold, tin, copper and tantalum.

Chengxin claims on its website that the Sabi Star lithium and tantalum project is “designed to produce 900,000 tonnes of raw (lithium) ore per year, equivalent to about 200,000 tonnes of lithium concentrate.”

Investigations carried out in partnership with Information for Development Trust—which supports investigative reporting on public accountability and foreign interests in Zimbabwe and Southern Africa— established that Sabi Star Mine was granted mining rights on 55 mining claims on 3 October 2018.

The area covers 3, 800 hectares in Ward 12 and the firm acquired certificates of registration for the mining claims which vary in size in areas that include Gonda, Bepe and Majere on 18 July 2019.

These claims had, however, been registered at the Mines ministry as far back as 8 November 2000 under Mezzotin Minerals Inc.

Chengxin has a 51 percent interest stake in Sabi Star Lithium Mine through Max Mind Zimbabwe, which is headquartered at 15 Harare Drive in Chisipite, Harare, and Liu Zheng is the local head.

Max Mind Zimbabwe has already injected more than US$80 million into the lithium project, according to Oswald Makonese, the mine manager, who in May indicated that Sabi Star would be commissioned in August.

Sabi Star mine entrance

We was robbed

The lithium project displaced at least 40 families that were relocated from Ward 12 to different areas.

Investigations established that 22 were moved to Murambinda, one relocated to Mberengwa, a rural district in the Midlands province, while 17 went to new homes in Tagarira and Mukwasi villages.

But those that have been relocated say they were ambushed.

Max Mind Zimbabwe signed a High Court draft order addressed to the affected villagers on 23 March 2022, citing them as respondents in their individual capacities.

The draft was initially stamped by the High Court on 7 April but quickly cancelled before being granted once again the following day.

This effectively paved the way for the relocation of the villagers and cemented an agreement for compensation and relocation of the respondents in terms of Section 80 as read together with Section 31 (1) (a) on the Mines and Minerals Act (Chapter 21: 05).

Sabi Star Mine officials Elfas Mugova and Kholwani Dube, Buhera district administrator (DA) Freeman Mwaemudza Mavhiza, village head Tagarira and Chief Nyashanu were some of the officials who attended the meetings that paved the way for the relocation of the villagers.

The relocated communities claimed that they have no minutes of the meetings that they held with the mine officials, mines ministry and local leadership but they confirmed being consulted.

They also acknowledged that they had signed agreements to relocate.

The problem, according to them, is that they hardly understood the contents of the agreement and were not legally represented.

An overture by one of them to have a family member who is also a lawyer to stand in for them was allegedly spurned by the district administrator.

“We tried to even get our own lawyer who is my young brother to assist us in the negotiation process but the DA was not happy. Whatever our chief and the DA says goes, so we were disempowered,” said Shame Masokozi Chamunorwa, an affected villager.

The villagers dismissed the claim by Mavhiza, the DA, that a committee represented them.

They said they were made to sign the relocation agreements just a day before they were moved, when the mining company revealed that the relocation fee of US$1,000 each was ready for disbursement.

This left them with little time to read through and understand the contract.

“We only got to view these housing units a day before we moved in after we had refused to vacate our homes arguing that we had not been shown the houses. We had to move because we did not have a choice,” said Itai Murwira, one of the relocatees.

Mavhiza, though, dismissed the allegation that the villagers had been shortchanged.

“It’s news! My understanding is that they had a committee representing them on what they were supposed to get as relocation package. They should use that committee to re-engage the mine and air out their concerns. I am available to assist that process,” he said.

That, however, looks like dead rubber because there is a clause in the agreement that stipulates that the relocated villagers “shall not have any further claims against the miner in respect of compensation and… relocation to pave way for the miner’s mining activities.”

The relocation contract is silent on the fate of the adult children of the relocated families.

“They compensated our elders but as children, we have nothing. We are above 18 and already have our own families. I am married and I have my own children but we are staying with our mother.

“The assumption was they would compensate each family including the children from that family. The mine shortchanged us. We can no longer go back to the village because we no longer have any home or land there. We are now forced to squatter with our parents,” said Tendai Mupengo, one of the villagers.

The victims allege that, during the negotiations, the mine misrepresented facts on who would be compensated.

Sabi Star negotiator at the time, Kholwani Dube, claimed that he could not comment because he had left the company, but his Linkedin account shows that he is still a geological technician at Max Mind.

Several attempts were made to talk to Chief Nyashanu and, on three of the attempts, a woman who said she was his wife claimed he was at Sabi Star on unspecified business, indicating frequent visits by the traditional leader to the mine.

The chief had not responded to a Whatsapp message sent to him on a number shared by the wife, to also enquire if it was true that he had been built a house at Murambinda by the mine.

Promises and lies

In the High Court order, Max Mind Investments Zimbabwe Private Limited is represented by Mugova, who is cited as the firm’s project manager, while the firm’s lawyers are Gill, Godlonton and Gerrans legal practitioners.

According to article 1.1 of the compensation agreement signed by both parties, the miner was obliged to meet the cost of compensating for the property occupied by the targeted evictees in Ward 12.

The provision stated that the property to be developed by the miner and used to compensate the occupier in Murambinda was to measure 450 square meters.

Murambinda houses

However, as our observations in the relocated area in Murambinda revealed, the 22 affected families were awarded stands measuring only 327.62 square meters, meaning that they were prejudiced of a collective 2 692.36 square meters, enough space to accommodate 8 more stands of an equal size.

Investigations also established that the houses that the villagers were allocated were already cracking, barely 4 months after moving in. In some of the houses, the floors are already rising.

cracking walls

“They came and patched the walls but the cracks keep coming back. The floors were poorly done and they are rising,” said Francisca Dube, one of the beneficiaries.

The outside toilet wall are cracking too and the relocated villager fear that they may cave in and collapse.

Forgotten orphans, lost livelihoods

Tariro Hapanyengwi, another villager, said she had engaged—with no successes—the mine over her orphaned neighbors who were not compensated for the structures that their late parents had left for them in Ward 12.

The children could not be located by this publication as they had moved to an unknown place “in the city”.

“I raised this issue with the mine and they know about these two children. They are now homeless. They were not given anything because they are in the city but this was their rural home. The mine did not compensate them,” she said.

The relocation contract obligates Sabi Star to meet “any of the relocation costs associated with movement from his current place of residence to the new property”, household goods, agricultural assets and livestock included.

In addition to the US$1,000, the villagers were given monthly payouts of US$150 for six months.

But the relocations to confined spaces means that the families have lost the land that they, for decades, depended on for survival through farming and other livelihood activities.

They tilled the land as subsistence and small-profit farmers, sold fruits from their household orchards and engaged in other income activities that kept them going over generations.

They have, all of a sudden, been forced to look for other livelihood opportunities.

And the relocated families are bitter that they were forced to leave their livestock behind, in the custody of relatives and former neighbours.

Some of the relocated famikies have built small structures to accommodate small livestock.

Below, cattle left behind

“My cows and goats are still in Tagarira village yet they had agreed to take them to Chahwa (another village). I am paying the people who are keeping them for me back,” said Jestina Kemba.

Title deeds

The relocated families said they were yet to get title deeds for their new homes.

Several women accused the mine authorities of sidelining them and choosing to acknowledge and deal with their husbands only.

“As women, we are not represented neither do we have a say. Our names are nowhere in the contracts. Should my husband wake up with another wife, how will I claim ownership of this house? I am sure that even if we are to be given the title deeds, they will be bearing the husbands’ names while excluding us as spouses,” said Emily Ngorima.

The mine officials and Buhera town council CEO refused to comment on why the families were yet to get their title deeds.

They did not divulge the criteria that had been used to select the men and women cited on court papers from each family.

The firm’s human resource officer, Knight Muchakata, ignored several requests for comments but acknowledged receipt of interview questions.

He said the questions had been sent to the relevant departments but there were no responses almost three months after.

A source, however, told this publication that mine officials visited the relocated families at Murambinda growth point and measured the houses a few days after getting questions from this publication.

Contaminated borehole water?

Maxi Mind Zimbabwe sunk several boreholes at local schools and four more at different homesteads belonging to the relocated families but beneficiaries are complaining about water, which they is muddy.

This publication took samples of the borehole water, which turns yellowish with time.

“Those who are working at the mine get drinking water from the mine. For us who do not have anyone working at the mine, we are forced to drink this water,” said a relocatee.

The relocated families suspect that the water could be responsible for sporadic diarrhoea cases in the area.

The villagers expressed dismay at the mine for failing to employ locals.

Buhera Rural District Council chief executive officer, Emily Chibvongodze, refused to comment citing fears of victimisation.

“There was a time I mentioned a community project being done by the mine on national radio and I was reprimanded,” she said.

This story was co- published by The Standard Zimbabwe working in collaboration with IDT

Comments are closed.